It’s time for the CA/Browser Forum to focus on the other half of its mandate

Let’s have a candid discussion about Extended Validation SSL. What’s working. What’s NOT. And what can be done to fix it so that all parties involved are satisfied.

But first, let’s zoom out and talk big picture. The vast majority of website owners almost never think of SSL. They worry about it once every year or so when it needs to be replaced, but it’s not really a major point of consideration. And even when it is, it’s on more of a macro level when managing certificates at scale. Most site owners and organizations don’t care about industry politics or what’s going on at some Forum in the same way that we don’t give a toss about what’s going on at the American Dairy Association. As long as there’s milk on the shelves we just assume everything’s fine.

Right off the bat, we can admit that some of the arguments put forth against EV are valid to some extent. But we also believe that identity is a major component of trust – a component that’s even more critical on the internet. That’s why – in light of the complete lack of alternatives – we think fixing EV is a worthy discussion. We think this proposal is a reasonable way to address most of the major criticisms leveled against EV by its critics.

So, today we’re going to talk about Extended Validation and what can be done to fix it. Then we’ll propose several changes to hopefully kickstart a larger conversation.

Let’s hash it out.

Is Extended Validation fulfilling its purpose?

Let’s start out with a quick overview of what specifically Extended Validation SSL is supposed to be accomplishing. This is the definition as it appears in the CA/Browser Forum’s EV Guidelines:

The primary purposes of an EV Certificate are to:

- Identify the legal entity that controls a Web site: Provide a reasonable assurance to the user of an Internet browser that the Web site the user is accessing is controlled by a specific legal entity identified in the EV Certificate by name, address of Place of Business, Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Registration and Registration Number or other disambiguating information; and

- Enable encrypted communications with a Web site: Facilitate the exchange of encryption keys in order to enable the encrypted communication of information over the Internet between the user of an Internet browser and a Web site.

Ok, so, number two is really just a basic function of any SSL certificate. It doesn’t matter if it’s DV, OV or EV – they all facilitate encrypted connections. It’s the first purpose that we’re really debating when we discuss Extended Validation.

So, let’s break it down like this:

Does EV identify the legal entity behind the website? Yes.

Is the way it presents that information – as well as sometimes even the information itself – confusing? Yes.

And that’s really the biggest point of contention.

Where some CAs are making a mistake – and please excuse our candor here – is focusing on the secondary purposes as they advocate for EV. In case you don’t have your copy of the EV guidelines handy, here’s what the secondary purposes are defined as:

2.1.2. Secondary Purposes

The secondary purposes of an EV Certificate are to help establish the legitimacy of a business claiming to operate a Web site or distribute executable code, and to provide a vehicle that can be used to assist in addressing problems related to phishing, malware, and other forms of online identity fraud. By providing more reliable third-party verified identity and address information regarding the business, EV Certificates may help to:

- Make it more difficult to mount phishing and other online identity fraud attacks using Certificates;

- Assist companies that may be the target of phishing attacks or online identity fraud by providing them with a tool to better identify themselves to users; and

- Assist law enforcement organizations in their investigations of phishing and other online identity fraud, including where appropriate, contacting, investigating, or taking legal action against the Subject.

The extent of EV’s relationship with phishing is debatable, but continuing to harp on this distracts from the better part of the argument – that a mechanism for asserting identity is critical for the internet’s trust ecosystem.

That point is a lot harder to contend with, which brings us to …

Criticisms of EV

Generally, criticism of EV falls into one of three categories:

- EV UI takes up real estate in the browser’s address bar

- People don’t notice or don’t know to look for EV UI

- The validation portion of EV is broken and unreliable

And again, each one of those criticisms has some validity. So, we’re going to take an objective look at each one before we lay out our proposal.

EV UI takes up real estate in the browser’s address bar

This is a criticism first leveled by Google during deliberations at the CA/B Forum.

So the whole premise for why there should be *any* UI treatment is predicated on 2.1.2 (2), which clearly spells out that EV is a marketing tool, wrapped in the guise of a security tool. I do not feel you can offer a more charitable read of that section … Literally the entire value proposition of EV reduces to “CAs want to sell billboards in the browser’s security UI”. And the fundamental point is that such UI is security critical – it’s the line of death between trustworthy and untrustworthy content.

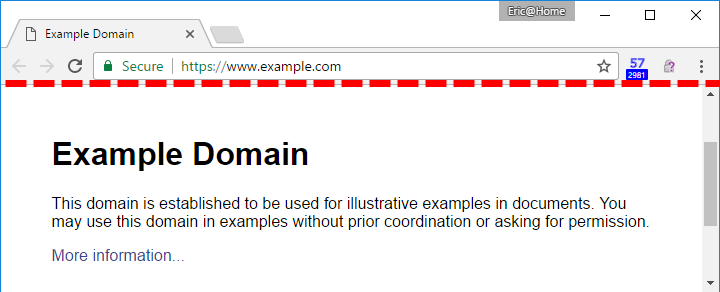

What Google’s rep just alluded to is a concept that is fairly sacrosanct to many in the browser community. Eric Lawrence elaborates on in a blog post:

If a user trusts pixels above the line of death, the thinking goes, they’ll be safe, but if they can be convinced to trust the pixels below the line, they’re gonna die.

Everything above the red-dotted line is under the browser’s control, everything below it is untrusted content. That’s not to say that it’s necessarily malicious, just that the browser has no control over it. If one of the primary functions for any browser is to keep its users safe, ceding this much of the window only complicates that objective.

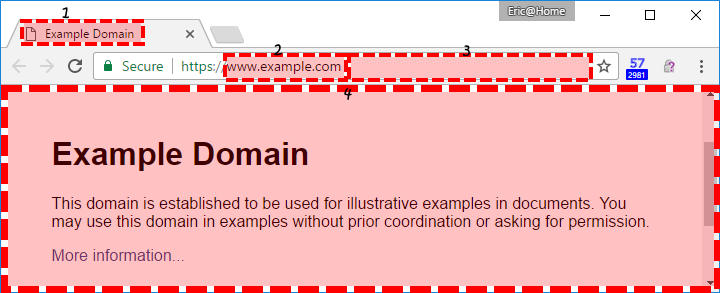

The reason Google is so sensitive about the space that an EV Visual Indicator occupies is because the browsers are already allowing some untrusted data to live above the line of death now, too. Lawrence illustrates this concept by creating zones:

As Lawrence terms it, an attacker has control over all the zones in red, leaving the browsers very little real estate to try and keep a user anchored and safe. If the browsers are going to continue renting space to CAs for a unique visual indicator, they want to make sure that there is sufficient value in that arrangement.

That’s totally fair.

And we’ve taken that into considering with what we’re proposing. I think it’s a bit cynical to say the CAs just want to sell billboards, but that’s pretty on-brand for the CA/B Forum. Moving on …

People don’t notice or don’t know to look for EV UI

We wrote last week about the general lack of civility at the CA/B Forum, as well as the fact that any research put forward by the CAs is judged to be tainted and unreliable. It’s treated like junk science.

And the rest of the Forum talks about whether the EV indicator is useful like it’s been empirically proven.

Here’s the thing: it hasn’t.

Measuring whether or not people notice or use a trust indicator is incredibly difficult to quantify. You can’t do it with a survey.

The human brain can process images it sees for as little as 13 milliseconds. As Nicholas Rule, a social psychologist that teaches at the University of Toronto, writes in the Association for Psychological Science’s Observer Magazine:

Before we can finish blinking our eyes, we’ve already decided whether we want to hire, date, hate, or make friends with a person we’re encountering for the first time. These first impressions color the way we interact with other people from that point forward. And all of this happens outside of our awareness, in the unconscious processes of the mind, research shows.

But that’s first impressions of people. What about websites?

The average internet user forms a trust decision within 50 milliseconds of arriving on a website. This according to a study performed by the Human-Oriented Technology Lab at Carleton College and published in the journal, _Behaviour & Information Technology.

Our minds process millions of things on a daily basis on a sub-conscious level. This is called subliminal stimuli, it occurs beneath our threshold for conscious perception.

As Karin B. Jensen – who has a PHD in Neuroscience and teaches Psychiatry at Harvard – wrote in the International Review of Neurobiology just last year:

Subliminal means that a stimulus is presented below (sub) the threshold (limen) for conscious recognition, yet the stimulus can still affect behavior as it has been registered at a basic level of perception …

The point I’m making is NOT that EV registers on a subliminal level. It’s that WE DON’T KNOW.

I’ve just cited science that was rigorously researched and reviewed by experts in their respective fields. By contrast, this is the methodology employed by Google in the study that’s widely cited as showing the current security UI doesn’t work:

To motivate the need for new security indicators, we critique existing browser security indicators and survey 1,329 people about Google Chrome’s indicators.

So, to be clear, this is just a survey. Conducted by Google polling its own customers. And the phrasing “to motivate the need for …” sort of feels like Google already knew what it was hoping to find before it even started its survey. This would be considered tainted if it had come from the CAs. But petty grievances aside, this is far from scientific. It’s tough to get exact figures on how many users Google Chrome has. But its mobile app alone has been downloaded more than 5 billion times. I mention this because 1,329 people is an infinitesimal sample size. And it’s not measuring any of the cognitive aspects of the decision.

Asking someone “did you notice this” is unreliable. That’s why witnesses are often discounted in criminal trials. There’s a proven disparity between what we process and what we remember. Even the godfather of user research himself, Jakob Nielson (no relation to Leslie) once wrote:

Too frequently, I hear about companies basing their designs on user input obtained through misguided methods. A typical example? Create a few alternative designs, show them to a group of users, and ask which one they prefer. Wrong. If the users have not actually tried to use the designs, they’ll base their comments on surface features. Such input often contrasts strongly with feedback based on real use.

Case in point, I drive 45 minutes to work each morning. On the way I make use of all kinds of symbols and indicators to help me navigate, but if you stopped me the moment I got out of the car and showed me a picture of a sign or symbol I drove past on the way, I couldn’t tell you if I remembered it or not. And even if I could that would be unreliable because you didn’t actually see me use it that way.

I also couldn’t tell you if I’d noticed it had been removed. But the corollary of that isn’t that it’s not useful. That’s taking a leap.

Most of the “research” on this topic is just anecdotal or its methodology only scrapes the surface of the human judgment process.

Again, the point I’m making ISN’T that the UI does or doesn’t work. It’s that the research we have on both sides of the debate doesn’t really prove anything.

The validation portion of EV is broken and unreliable

This point has some substance – but it’s overstated. And none of it is “un-solveable” as some so adamantly claim. Specifically, when it comes to EV SSL, there are two major points of contention here.

- The process can be exploited by attackers

- The information provided can be confusing

Let’s start with the first one, that the process can be exploited. Ian Carroll and James Burton both produced proofs of concepts that showed how the EV system can be abused. Burton created a misleading organization name. Carroll created a naming collision. Technically both Burton and Carroll’s exploit checks both boxes because the verified information is also confusing.

At the time, Burton opined:

EV is on borrowed time and deprecating EV is the most logical viable solution right now and brings us one step forward in vanishing the old broken web security frameworks of the past. Now that both me and Ian have demonstrated the fundamental issues with EV and the way its displayed in the UI, it’s only time until the REAL phishing starts with EV.

Now, please show me the data if I’m wrong, but that last part really hasn’t happened, has it? There hasn’t been an explosion of EV phishing. If you’re going to argue EV doesn’t stop phishing that’s fine, but it’s also not being used for phishing, either. The few cases where there’s been a rogue EV certificate were the result of site compromise. And there’s a bit of conflation with the EV code signing certificates for sale on the dark web and EV SSL certificates. The latter is not all that prevalent. Again, show me the data if I’m wrong.

While the validation portion of EV (and pretty much all SSL) could do with some tweaking and improvements, you really do need to jump through a number of hoops to exploit it. (And many of those hoops require government filings, which criminals typically try to avoid.) And the point where things broke down with Carroll’s POC was with the UK Companies House – not the CAs.

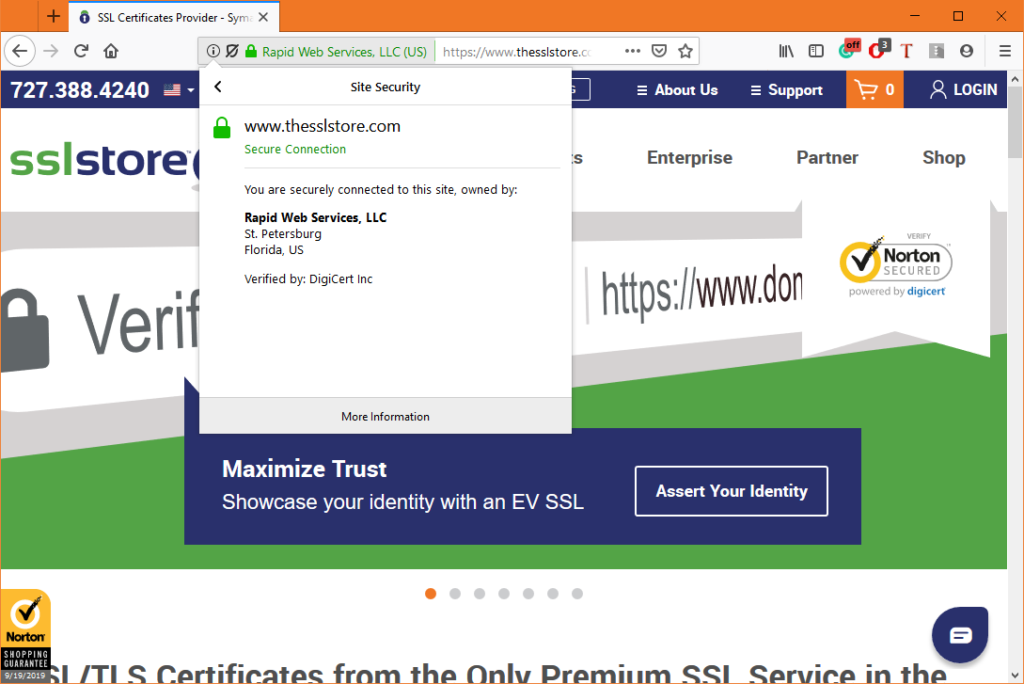

The other criticism is that sometimes the information provided by EV can be confusing. Carroll’s exploit was confusing because it created a name collision with the Stripe payment company. The SSL Store™ deals with this, too. The SSL Store™ is a DBA, so our EV name plate says “Rapid Web Services, LLC.”

Our proposal: Mouse-over UI with LEIs included

Our proposal really has three prongs, we just didn’t feel like putting the third in the header because education just isn’t all that provocative (really, none of this is).

- Mouse-over UI

- Browser Home page educational messages

- LEIs

Like we did with the complaints, we’ll go through each of these suggestions one-by-one. Each is made to help address the major criticisms opposing EV.

Positive mouse-over EV UI

Let’s start with the actual UI suggestion, which is to place the EV UI in a mouse-over or hover-over box that displays the first time someone mouses over the address bar, and then again when someone hovers over it for a couple of seconds. The indicator should also be differentiated with a positive symbol, too. Ideally something like Apple’s Safari UI, which presents EV URLs in green. This would indicate more information is available.

This approach has a few benefits:

- Doesn’t take up browser real estate

- Offers space to include more information

- It’s harder for users to miss

Nobody on the internet is clamoring for less identity information to be available. Well, nobody reputable. As more and more people become aware of data security on account of the never-ending torrent of breaches in the news daily, trust and identity are increasingly important. This would provide a surefire way to display some information about the organization running the website in a way that’s more noticeable to the user. If they don’t like it, let them turn it off with a flag or a setting, but most people will appreciate the expanded information.

Right now, Mozilla offers a solid model for how this could go:

Unfortunately, in its current iteration you have to click on the padlock, then on the little arrow next to the connection field. And most people really don’t know where to look to find it this way.

But if you start showing this data the first time someone mouses over the address bar they’ll start looking for it. Aesthetically the browsers can do it however they want, but if we at least partially standardize this approach some of the education takes care of itself, once people notice it’s there they’ll find it useful.

That brings us to …

Educational messages on browser start pages

When you open a web browser it takes you to a start page with some favorites, maybe some news – but plenty of unused real estate. Consider that 95% of people never change their default settings and statistically that means 19 of 20 internet users are seeing the same screen when they start up.

The other thing these pages have in common, which we just alluded to – besides the fact almost every browser user sees them on a regular basis – is that they have a lot of empty space.

And that space would be a perfect place to stick a small message advertising this new feature. Some browsers already display informational messages like this:

Because one of the misnomers that comes with the “people don’t notice/know to look for it” argument is that the CAs have somehow failed to educate their customers about EV. But the CAs HAVE educated their customers. That’s why some organizations use EV in the first place. It shouldn’t be incumbent upon the CAs to educate the browsers’ customers. Should they do more? Probably. Is it solely their responsibility? No, the browsers need to be doing it, too. This is a partnership, SSL certificates are a support product. CAs don’t have a mainline to the browsers’ customers, the browsers do.

And frankly, educating users shouldn’t even be that hard. Again, a quick notification on the Browser Home page should be sufficient. But we need to standardize a UI first or no amount of education is going to have the intended effect.

Add LEIs to certificates

There’s a ballot at the CA/B Forum right now that’s debating whether this should happen. Here’s some background: LEIs are Legal Entity Identifiers, they were created in the aftermath of the financial crisis that occurred a decade ago. They are numerical codes recognized by 150 different countries. The entire system is overseen by a Swiss non-profit called GLEIF. The numbers are divvied out by Local Operation Units (LOUs).

Given the overlap between issuing digital certificates and issuing LEIs, a number of CAs are already operating as LOUs. Unfortunately, there’s one recalcitrant member of the forum that’s gone so far as to suggest they will unilaterally block this ballot and potentially distrust CAs that issue certificates with LEIs included.

It’s hard to understand why. An LEI can help prevent collisions and confusion. As Stephan Wolf of GLEIF wrote in a recent CA/B Forum email:

The whole point of including an LEI is efficiency so organizations have a uniform, globally recognized and standards based unique 20 digit identifier that is machine readable, will never be reused, and can be used to access other data using the same number.

Now, I can already hear the objections percolating, that, like confusing organizational names, people won’t know what to do with an LEI number. But there are several workarounds for that.

For one, the browser could just use the LEI code and generate the associated information. Granted that might require an additional call, which may be anathema to browsers – but it’s an option. You could also make it easy to click on the LEI number and follow it to a database with the information. This would require the user to take an action, but some might find it useful. But more than anything, it could send up a red flag when an eCommerce website or some other organization that transacts in valuable data DOESN’T have an LEI.

Again, this debate is still in its infancy – but as Wolf wrote to Google:

The LEI should be embedded in other eco systems for the greater good. I would like to state that LEI adds another layer of trust to EV certificates. Given your concerns about trust and evaluation, you should put yourself at the forefront of this project. The LEI has a lot of value for the Google user base among more.

Does anyone have a better idea?

The final point we’re going to make is about the CA/B Forum itself. Last month we made a case for a return to civility. Pretty much just asking everyone to stop acting like assholes. But one of the things we mentioned in that article is that the CA/B Forum is really only fulfilling half of its mandate. From its own bylaws:

The Certification Authority Browser Forum (CA/Browser Forum) is a voluntary gathering of leading Certificate Issuers and vendors of Internet browser software and other applications that use certificates (Certificate Consumers).

Members of the CA/Browser Forum have worked closely together in defining the guidelines and means of implementation for best practices as a way of providing a heightened security for Internet transactions and creating a more intuitive method of displaying secure sites to Internet users.

And here’s the thing, nobody that’s advocating for the end of EV has any kind of constructive suggestions for how to accomplish what it was designed for. And what EV is trying to do is pretty universally regarded as a good thing. It’s just a matter of its efficacy.

If there was a competing approach that was being served as a replacement that would be one thing. But eliminating it without any vision towards a replacement does not make the internet safer or more secure. And that’s not in line with the Forum’s stated goals. It seems like discarding EV with no viable alternative just sets the whole internet backwards.

The internet can’t afford to wait for us to figure something else out. Again, identity has never been more critical. If you have another way to approach authentication and ID online, let’s hear it. Otherwise, we should start figuring out how to fix EV. Most of the CAs want to have that conversation. Whether or not it actually gets discussed – and earnestly – is up to the browsers.

As always, leave any comments or questions below …

This post originally appeared on Hashed Out by The SSL Store. Republished with permission.